It’s hard to lay eyes on John Brown Canyon, on even the clearest of days. The Central Oregon gorge is remote, four miles long, with a thin creek called Campbell running through it. Just south of Highway 26, it’s in shouting distance of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. Until just two years ago, the essence of this Jefferson County physical feature, which meanders down to the Deschutes River, just north of Madras, was even more difficult to see.

The name of the 900-acre canyon was part of the problem: “John Brown Canyon” wasn’t on a map. Residents in the region would hear the canyon’s other names in passing. Elders might recall reading its original name in the newspapers of Madras or Bend: Nigger Brown Canyon.

Until 2013 the spot was still on maps as Negro Brown Canyon—an improvement of a kind, but not the sort of name for a landscape feature capable of drawing positive attention. Around this time, the Oregon Geographic Names Board was deluged by requests to rename geographic features with the pejorative “squaw” in their titles. Board members found themselves just as intrigued by a name change proposed by a local elementary school teacher and a college English teacher from Central Oregon.

“My first impulse,” says historian Jarold Ramsey, “it was to address a wrong. It was monstrous that, at least orally, the physical feature of the canyon was called Nigger Brown Canyon.”

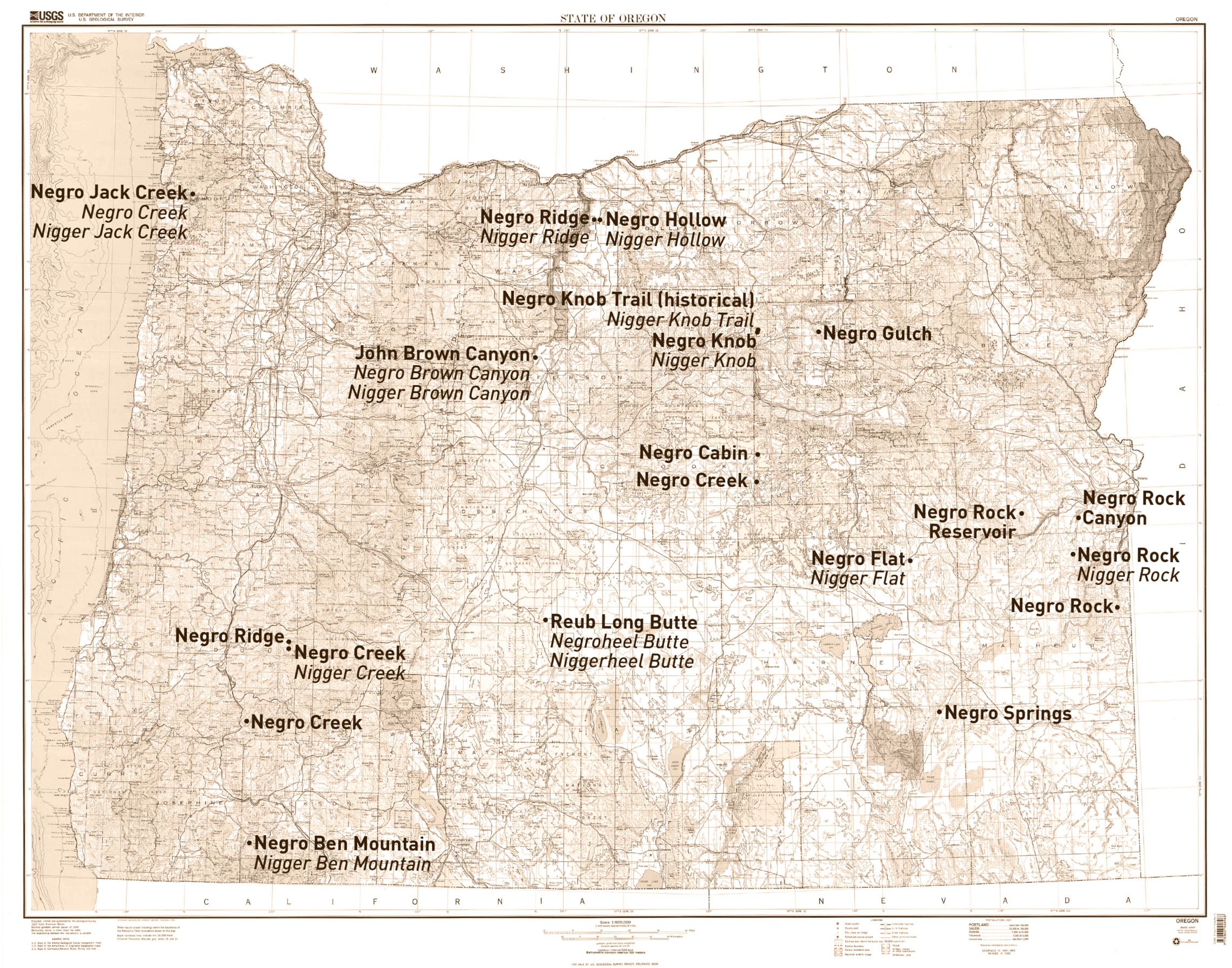

This map shows geographical landmarks in Oregon that have had “negro” or the n-word as part of their official names. Current names are in bold, and past names are in italics. Map by Paste in Place/Ryan Sullivan

In the journey toward justifying the name change, the educators learned about John Brown. He was a nineteenth-century adventurer bold enough to escape slavery, then return to seek his fortune in America. In his last act, he has illuminated Oregonians’ sense of place.

The Agency Plains home Ramsey grew up in overlooks the canyon. He left Oregon for the East Coast after high school, but returned upon hanging up his textbooks in the early 2000s. Ramsey says it was one of his daughters who spurred the name-change effort when she complained about the racist appellation on a summer visit. But retired grade school teacher Beth Crow was the one who tracked down John Brown’s canyon homesteading claim and title to the land.

John Brown’s story is difficult to piece together based on historical records. Some sources say he was born a slave in Georgia in 1839 and that his parents escaped plantation life and whisked him away to Canada, where there was a community of freed slaves. The idea of returning to the United States must have seemed preposterous to Brown’s Canadian kin, but what is documented is that he crossed back over the Canadian border and put in a homesteading claim in the relatively unpopulated Central Oregon location. Ramsey supposes Brown had come to be part of the Oregon Gold Rush.

Crow and Ramsey continued their research, with Crow drilling down on census reports, voting records, and other paper documentation, and Ramsey focusing on gathering a number of surviving, local John Brown stories.

Together they learned that John Brown filed a claim in 1881 and eventually gained title to the 160 acres near the mouth of the canyon, making him the first African American homesteader in Central Oregon. Brown and his wife, thought to be Native American, had a daughter in the mid-1880s. Brown farmed the land as a truck garden, growing vegetables and fruit to sell at market in Prineville, a sixty-mile round trip. His garden was irrigated, one of the earliest in the area. Prineville is also where Brown, who was literate, voted on a regular basis.

Brown and his family left the area in the late 1890s, turning up later as a prospector in what is now the Sunriver area; places in that area officially bear his name. He died in 1903 and was buried in Prineville. A few years ago, the Crook County Historical Society erected a monument to him in the Pioneer Cemetery just north of town.

Ramsey reached out to the last living person who might have known John Brown: his former neighbor, John Campbell. Campbell’s family homesteaded a property that abutted Brown’s farther up the canyon. Campbell remembered Brown as a frequent visitor at the Campbell place, and recalls the day of Brown’s last visit: “One day, probably in the late ’90s, he came to see my dad and said, ‘I’ll be gone for a while.’ Only, he never came back.”

Crow and Ramsey took their seven-page application, along with the approval of Jefferson and Crook County’s Historical Societies, to the Oregon Geographic Names Board, which would make a recommendation to the US Board on Geographic Names if approved.

“When the case of John Brown Canyon came up,” explains Phil Cogswell of the Oregon Geographic Names Board, “we saw the proposal and we worked through it and we saw that it was appropriate to put John Brown’s name on it. We had hoped to put on it John A. Brown, to keep from being confused with the famous John Brown. But the US Board doesn’t really care for middle initials.”

That middle initial is the sole aspect of the effort that failed. In November of 2013, a few months before Beth Crow died, the board approved the name clarification.

There’s a yellow rose bush on the floor of John Brown Canyon. It's as big as a Beverly Hills swimming pool and taller than a full-grown human. John Brown planted that. In the spring you can see it bloom, like a reminder. Canyons are strewn across Jefferson County. Its most notable gorge may well come to be this one.

Comments

7 comments have been posted.

Before Brown Homesteaded this canyon there was a name in place already for it by human beings. If you could, please contact the local native american expert on the area and before making the legal documented great american and oregon name change please consider its first name as its real name.... Also- Please do this across the whole country! and oh yes... hurry up. GOD

Eric Gibson | July 2021 | Heaven

Thank you for this article and your research. I live in Central Oregon and this past MLK day, I took a drive to find his canyon and then visited his grave in Prineville. I can say Mr. Brown knew what he was doing. What a beautiful and perfect location. I also could not help imagining what his life was like here as a black man and knowing how racist Oregon was at the time. To then have several places named for him. He must have been quite a man.

Gordon Price | February 2021 | Bend, Oregon

I rly appreciate this. Thank you for your research and work!

Rachel Lee-Carman | June 2020 |

Thank you, Donnell and Sitka, for your contribution to correcting a "wrongness" in our world. I'm so glad to be considered a Friend, Donnell! To 'anony mouse:' Yes, People of Melinated Skin Tones do still receive prejudicial and racist treatment traveling in rural areas of Oregon. As a Troubadour, I have set feet in places where I have been the only person of African-American heritage within a 100 mile radius- pins and needles don't describe the situation- it is more like dancing on the edge of a knife, under the scrutiny of fire-breathing dragons.

Marilyn Keller | April 2017 |

I so appreciate that you shared your research with us - and I especially cherish that you conducted the research to begin with...despite its "white" appearance, many of us "native borns" have a significant interest in the stories and records of those who really pioneered the area, and who were part of growing to where we are now. The state has such rich history and so much to see and share...my late husband, who was termed "Black" was probably more than a little "white" - but a more loving man than any I had ever met...before or since! Our blended family includes everyone who calls themselves our "cousins" -

Lyn Horine | March 2017 | Salem

Thank you for this very important article, video and all of the work to finally pay homage and respect to Mr. Brown and his family. We have a responsibility here in Jackson county to do the work to change the names of " N Ben Mountain " as well as " Dead Indian Road". The change to " Dead Indian Memorial Road" has still not addressed the racist stigma of the name. Hopefully, we can do our part to move Oregon geographic sites' names to respect for all of its citizens, living and historical.

Laura Baden | March 2017 | Ashland

This was a great piece! Thanks for sharing this bit of history and continuing to open up our state's conversation about race. However, was put off that the Black woman commentator in this film implied that John Brown Canyon is in the middle of nowhere, that there's nothing much out here, nothing worth seeing. We who live out here see it differently. I thought, why couldn't they interview an African-American who knows about rural Oregon, who likes it and cares about it? Then I thought, Oh that's right. Not sure it's true any more, but this is known as the territory of white people, bigots, homophobes, Trump voters. I wonder if it's really like that these days? It would be nice to see a film about experiences people of color have outside of Portland and the larger cities. When I was growing up in rural Oregon 30 years ago, many folks including me and my friends didn't feel safe in many places. We were white but had funny hairdos and clothes. Some of us were gay or bisexual, before the days of Ellen DeGeneres being "out." Cowboys would call us "faggots" and intimidate, threaten, sometimes hurt us, throw things at us, stuff us into a garbage can. I always wondered, is this happening to people with darker skin, too? Are we all walking on pins and needles when we stop in a small town on our way to a camping trip? An adult now, I wonder, if people can't be bothered to change this perception of rural Oregon on a moral basis, maybe an economic argument would sway them. How many tourists avoid areas because of these fears? How many of those fears are well-founded?

anony mouse | March 2017 | Jefferson County

Add a Comment