When I was thirteen, a new face appeared in church. Her name was Coletta, and she had been a nun before leaving her order to attend clown school in Denver. There she had learned to be a mime and worked as a street performer for a year before moving back to Rapid City to be close to her family. One day, after mass, there was an announcement that she was starting a Christian clown group, and anyone, children as well as adults, were welcome to join. My siblings and I exchanged excited glances. It was as if God had invited us to join the circus. Who would say no to that?

I was in middle school. On my first day, a boy stopped me in the hall to tell me I was ugly. He was more or less pleasant about it, said my hair was nice but my neck was too long and I had no tits. I knew my breasts were small, but my neck? I looked at in the bathroom mirror. He was right! It was freakishly long, and I had never even noticed it before. To make matters worse, I had grown three inches in a single year and we didn't have enough money to buy new pants. This was the time when it was popular to peg your jeans by folding them over several times. I did this with my too-short pants, which left them about midcalf. I stretched my socks up to meet them, hoping no one would notice. But my efforts to conform did not win me any new friends. The few friends I had relied on in elementary school had made new, exclusive alliances. They shot me guilty looks from across the cafeteria at lunch, and I often sat alone.

There was a table in the lunchroom where the popular kids sat, all scrunched together on one side. I watched them carefully, analyzing their behavior, trying to learn their secrets. I longed to sit with them and be one of them. And one day I came up with a plan of how I might infiltrate their ranks. The plan was simple. I would carry my tray to the empty side of the table and sit down on the far end. Over a period of months I would scoot closer and closer to the middle, an inch or so every day. In this way, the popular kids would get used to me so slowly they would hardly even notice it. By the time I made it to the occupied side of the table, we would be friends.

The next day, I carried my tray to an unoccupied end of their table and sat down gingerly on the opposite end. I did not even dare to look at them. There was a rustling at the other side of the table, and then all of them stood up and carried their trays to another table and left me sitting there alone. After that, I gave up my plan to infiltrate. I started eating my lunch in the girls' bathroom. In the quiet darkness of a bathroom stall, there was no one to look at me and no one to make fun of me. I felt hidden and safe.

At our first meeting with Coletta, we deliberated over a name. Laughter for the Lord? Jesters for Jesus? Merriment for the Messiah? After making a long list, we decided on Clowns for Christ. Coletta taught us how to put on full clown makeup, which involves layers of oil-based makeup and powder. We designed our clown faces. I had an orange nose with blue swirls on my cheeks and a heart-shaped mouth. I gave myself the name Patches and wore a Hawaiian shirt with a giant pair of men's overalls patched with scraps of cloth. I finished off the costume with a pair of my dad's old shoes that were so big I could hardly walk in them.

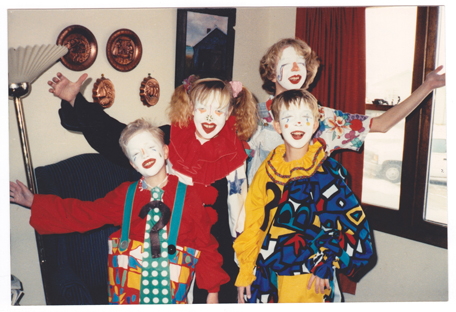

Beck family photo, 1991 (l. to r.) Jim, Bridget, Peter, and the author

There are two rules for being a Christian clown: The first is that once you put on your clown face you can't talk. The second is that when you're a clown, you have to let go of all of your problems and let yourself be moved by the Holy Spirit. We worked up a few skits and performed them after church to small audiences, which included my parents and a few other charitable souls. We did clown walks in public parks and the local Walmart. I loved being a clown, with the strange makeup, but most of all I loved making a spectacle of myself that was completely and absolutely anonymous.

When you're a clown, performing in a public place, like Walmart, most people won't look at you. Children are the one exception. Adults pretend that you're not there, because you kind of freak them out. They're just trying to get some groceries, and there's a clown in the middle of the aisle pretending to walk on a tightrope. Even though they ignore you, they're actually hyperaware of everything you do. It made me feel powerful. I carried around a jug of milk in my arms like a baby, showing it off to passersby like a proud mother. I pretended an orange weighed a hundred pounds and dragged it around the produce section. I could be as ridiculous as I wanted to be.

One day Coletta arrived with exciting news. Pope John Paul II was coming to Denver for World Youth Day. If we raised enough money, the troupe could go. So we began to fundraise. We had bake sales. We washed cars. We organized a “fastathon” where we tried to get people to sponsor us to go without eating for twenty-four hours. None of these ideas made more than twenty dollars. The application deadline was less than a week away, and we were nowhere close to having enough money. Then, out of the blue, an anonymous donor gave us the rest of the money. I've always thought it was from the Kateri circle, a group of Lakota women in our church, whose mission was the canonization of a Mohawk girl, Kateri Tekakwitha. They were always raising money to petition the Vatican by selling their beautiful star quilts.

Our little church seemed to attract people who were on the fringe of the Catholic Church. My family attended this church, instead of the fancy Catholic cathedral, because my dad was a Catholic priest. He had discovered his calling as a teenager. When sitting by a river the light changed, and my dad felt the strong, physical presence of God enveloping him. All his troubles melted away, and he felt a calm assurance that he would be taken care of, that everything would be OK. He entered the seminary at fourteen and became a Catholic priest when he was twenty-three. He was still a priest when he met my mom and they fell in love. After they married my dad left the active clergy, but he never renounced his vows. Because of his decision to marry, our family wasn't welcome at the cathedral. The priest there, who later became the bishop of Chicago, refused to give my father communion.

As I prepared to leave for Denver, I found myself hoping that I would have a spiritual experience of my own on our trip. I could picture it. The pope would be passing by, he would stop and lay his hands on my head, and it would happen: my religious experience. The yellow light would surround me and my problems with middle school and the popular kids would melt away.

When we arrived in Denver we were excited and a little bit scared. None of us had ever been to a big city like Denver before, and we thought there was a chance that we might be robbed. What if someone tried to steal the ten dollars in spending money my parents had given me? Just in case, I wore my fanny pack facing the front and kept one hand on it at all times. It was the middle of August and 103 degrees. We quickly abandoned any hope of dressing up as clowns because the makeup would melt in the extreme heat.

Christian teenagers from all over the world thronged the streets. We met a group who had traveled from Madrid. I wondered how they'd raised enough money to travel across an ocean, when we had barely made it from two states away.

The big event with the pope was going to happen in the football stadium. We flooded into the gates with the other teens and found a place high up in the bleachers. At this point, I abandoned my dream of having the pope lay his hands directly on me. But I did not give up hope of having a religious experience—I thought it could still happen remotely. It was the middle of the day and terribly hot. We were guzzling bottled water and people were passing out from the heat. At last the pope arrived. The stadium went wild, with people doing the wave, shaking pom-poms, and throwing flowers.

From our vantage point the pope was incredibly small, a tiny white figure standing up in a special car, encased in bulletproof glass. The car made a lap around the field and he stepped out and walked onto the stage. We watched him on one of the big screens as he approached the microphone and began to speak. He had a thick Polish accent and the speakers were reverberating in a way that made him almost unintelligible. I remember straining to get any meaning out of it. My head was buzzing with the effort, and I could hardly understand anything he was saying. To make matters worse I really had to go to the bathroom. But despite the pain in my bladder, I resolved to stay.

Then he finished talking and it was over. The magical experience I hoped would change everything hadn't happened to me. Before I could feel properly disappointed someone came up to the microphone and made an announcement that anyone who felt called by God should come forward and the pope would lay his hands on them. I couldn't believe it! I jumped out of my seat and started to work my way down the aisle. Then he spoke again, to clarify: “Any young man who feels called by God, who is considering becoming a priest, should come forward.” I stood there in disbelief as a stream of teenage boys passed by, forming a small crowd in front of the stage. The pope began to lay his hands on them.

I had been a clown for Him, but it didn't matter. God was just like the popular kids at school. What was the point of being a clown for someone who treated you that way?

The feeling I had was the same one I'd experienced in the lunchroom when everyone stood up at the popular table and left me sitting by myself. The religious experience that had happened to my dad would happen to all those boys waiting in line. Because I was a girl, it was not going to happen to me. I retreated to a bathroom, closed the door to my stall, and cried. I was angry and humiliated and confused. I had been a clown for Him, but it didn't matter. God was just like the popular kids at school. What was the point of being a clown for someone who treated you that way? I decided to give up clowning. But even as I considered this, my heart sank. I loved being a clown. In a flash of inspiration it came to me. I would continue with the clown troupe. I would go through all the motions of a Christian clown, but in my heart I would be a free agent. I would be a clown for everyone, and a clown for myself, but I would not perform for God anymore.

When I returned home, I started mouthing the words to prayers instead of saying them. When I ate the Communion wafer it was just a dry piece of bread in my mouth. It wasn't that I had felt a strong connection to these rituals before, but I had always thought belief was something I would grow into with the other mysterious trappings of adulthood. Now I considered the possibility that sitting in church was like waiting in a long and pointless line. And that middle school was not a fluke I would pass through with the help of divine intervention, but the real and actual truth of the rest of my life.

Through it all I continued clowning. I loved improv sessions because I liked connecting with people, especially children, who delighted in the unusual and unexpected. Through the character of Patches, I had permission to be myself in a way that was immune to insult. I was strange and silly and conspicuous. I was able to poke fun at myself without feeling that there was anything wrong with me. Although I did not recognize it at the time, this was exactly the gift I'd hoped to receive via a lightning bolt from the pope. When I was a clown I did not feel excluded, but at the center of things. If this feeling did not last when the makeup came off, the memory was still with me. Perhaps divine intervention had come when I needed it, after all. Not in the shape of the pope, but in the guise of a clown.

The summer of my eighth-grade year, Coletta decided to move to Las Vegas to become a blackjack dealer. Our final clown walk was in the city park. After an hour of improv, entertaining kids on the playground and surprising people trying to walk their dogs, the entire troupe packed into Coletta's VW bug and headed back to church. We stopped at a red light and watched as four lanes of traffic came to a halt, drivers and passengers staring at us in shocked surprise. There were two clowns in the passenger's seat, and four in the back (me and my three siblings: Bobo, Chuckles, and Lucky). Coletta was driving, wearing a soft red clown nose and a floppy green hat. No one even registered the light as we hammed it up, making silly faces, waving and gesturing, laughing so hard our stomachs hurt. Coletta caught my eye in the rearview mirror, and gave me an exaggerated shrug, as if to say, “What's the big deal? Just a car full of clowns.” The light turned green and we were off.

Comments

1 comments have been posted.

The story was like a broadway play... “I laughed, I cried!” I look forward to more stories from Ms Beck. What a very talented writer

Floyd | March 2019 | Portland Oregon